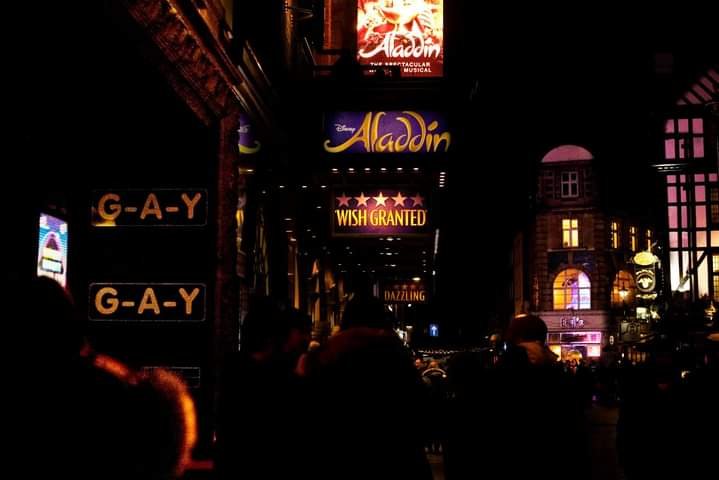

Over the years, I’ve photographed almost every famous street in London, but a great number of photos in my collection are of the West End where stage shows are known to run for a long time, sometimes decades. So, one might see the same theatre-billboards in my photos spanning over many years, then one day it will have changed. At Prince Edward’s, I’ve seen only three changes in 12 years, Jersey Boys to Miss Saigon, and then Aladdin. (I heard Mary Poppins is running currently, but I’ve not photographed the theatre in recent months).

Westerners (especially the young), when asked about Aladdin, claim to know who he is/was – a Disney character, obviously. They are right. He is a Disney character. But not to us Easterners.

We grew up reading Aladin ka Chirag and Aladin aur Genie, or the Forty Thieves, as part of our intra-and-extra curricula. Every household had Arabian Nights literature. In school, one year we would have essays on a portion of the One Thousand and One Nights, while another year we will spend on comprehensive study of Dickens’ David Copperfield. Even Don Quixote and Sancho Panza were sketched in our books and exhaustively analysed, down to Quixote’s horse’s hooves. It was as if reading the books was not enough, our young minds had to find the answers to all the whos, whys, whats, wheres, hows, and even whynots. I’m not even going to touch upon the topic of poetry, because if someone read my blog, they would scracely believe that we learnt every single poem by heart, as a stanza from anywhere from those 30 to 40 poems learnt each year could be asked in the exam. Literally, like this…

Q1. Write the title of the poem, the poet’s name, and complete the following stanzas…

One shade………… innocent!

Q2. Read the above poem and explain who, what, where, how, why and whynot.

(I’m pretty sure that Keats and Byron scholars made things up as they went along… to cause us frustration). (Okay, I did touch upon the topic already). And, why do people celebrate Shakespearean English that much but not speak in that?

Even so, despite the lengthy syllabus and ongoing frustration of coming up with gobbledygook explanations, English Literature and English Grammar (yes, that’s right. Grammar was a standalone topic) were my most favourite subjects, followed closely by Geography. Hindi was fairly easy too. Sanskrit was fun as we can show-off a bit, by reciting the ślokas to the non-learned. I never understood why I had to learn anything else. I suppose it was to help our kids one day with their school work. And, Maths! Where is that boy, Aryabhata? Bring him to me!! I’ll sort him out.

So, coming back to Aladdin…

I came across this photo of mine from one of the street adventures and was transported back to my younger days of The Arabian Nights nights, surrounded by many books, some with illustrations, while some without, in which case we imagined the magical scenes and the flying rugs. I had mastered the drawings of Genie and the magic lamp. I owned a similar brass lamp from Rajasthan (I’ve often compared things between Arabia and Rajasthan – desert, climate, camels, jewellery, cooking vessels, musical instruments, and also the music). Once or twice, I tried rubbing my brass lamp to summon the Genie, but a giant cockroach appeared instead from under the door, let in by my brother, who expertly disturbed my concentration. In retaliation, I would catch a lizard from the adjoining tree and let loose on him.

My room had a beautiful rug and my mind had the capacity to imagine beautiful things. I read somewhere that if I could learn the magic words in Arabic, I could make my rug fly, with me seated on it. So, I started to leave my verandah door open before uttering the magic words (in case the rug wooshed and started banging against the glass – I might have had a “crash” landing). But the rug never left the earth. It probably could not comprehend my rustic Arabic. The accent was too Hindi. I knew I had to brush-up my Arabic.

At the university, I had several Middle-Eastern friends. I tried to learn a little Arabic from them, but they were more keen to learn English from me. They did not crave the rug flight as much as I did. They probably had quite a few around-the-globe already, then hopped off on India.

One day…I’ll summon the jinni and get him to arrange a flight for me. And since I’ve waited so long, a detour would be appreciated. Moon maybe!

P. S. I never understood this… Genie is meant to be an imprisoned slave, a good guy in the Nights, then why do we in the East use the word ‘jinn’ as having negative connotation of evil, devil or unpleasant or monstrous spirit, a shaitan?

Whys for another time! For now, I’ll curl-up in bed and dream of flying and enjoying a bird’s-eye view of the planet. It’s an interesting way to put all things into perspective. My little worries won’t mean much from above. I’ll be just a speck, and my worries even smaller. Thank you, Aurelius.

… Sapna Dhandh Sharma